Impossible Objects

The Journal of Applied Impossibility

a blog. blahhhhg. blouuuuuggggh!

The Madness of Odysseus2/19/2019 Note: originally posted on my personal site. Date changed here to reflect original posting date as I migrate my blog here. He broke off and anguish gripped Achilles. I'm a boss-a** b****, b****, b****, b****, b****, b****, b**** I. A dear friend once described the willfully ignorant to me: “It’s as though they had super-powers!” It is strange, indeed to think how one can believe what one knows not to be so. It is somewhat akin to flying. Upon reflection, it is perhaps even more to be desired. For flying is sometimes dangerous, and one must leave the comforts of home. To be able to believe oneself to be flying without leaving the living room -- why, that affords all of the delights of both! And so it is that I am amazed when I have a conversation with people who are allegedly educated and are able to convince themselves of anything, regardless not merely of its truth, but regardless also of their own belief that it is true! The context of this description on the part of my friend was a conversation the two of us were having with a third party. My friend was (and is) a Christian. I was not (although I believed in God -- or rather, I believed that I believed). The third man was neither a Christian nor a theist, but a prospective graduate student interested in something called “theory.” Theory is much like philosophy, lacking only the earnest desire to pursue wisdom. Borges tells us that etymologies do not tell us what a word means, but rather what it no longer means. The etymology of theory comes from a Greek word for speculate and spectator. Thus, theory no longer means thinking about what one observes. It is not an attempt to understand what one takes as given by experience. Rather, theory is an attempt to decide what experience one wishes to have based upon what has not been given in order to avoid understanding the object theorized. This young man’s theory had convinced him that there is no evidence for the beliefs my friend held about Christianity, or those which I shared with him about the existence of God. The young man believed this because evidence would be something that is given, and could be observed. And without theory, once evidence is observed, we would need to consider what it means, and try to form beliefs about the world. Worse still, one may discover that beliefs one previously held do not stand up to evidence. That is, one might discover oneself to be wrong. But theory had bestowed its blessings upon this young man, and he was in no danger of discovering anything so dreadful. Helpless in the face of theory, my friend made a final attempt at communication. He asked the young man, “Am I wearing shoes?” The reader will perhaps believe that she is in no place to answer the question at this point, lacking an observation of my friend’s feet. But this is only because she suffers from perhaps too much philosophy, or at the very least from a dearth of theory. The young man was already adept at his theory, and promptly responded, “There is a perspective according to which you are wearing shoes. But there might also be a perspective according to which you are not. It would be unfair to judge between two such equally valid perspectives, and so I can only say that I don’t know whether you are wearing shoes or not.” II. This truly baffled me. It seemed silly that someone who is able to utter words with multiple syllables while walking and avoiding being run over by Chicago traffic cannot glance down for a moment to determine whether my friend is barefoot. Sillier still is the notion that there is a perspective about the matter or that all perspectives are somehow equally valid. I confessed my confusion to my friend, and he explained it me thus. Had the young man admitted that my friend was in fact shod (as he was), the man’s very world would have begun to collapse. For at this moment, there would be something true that even theory cannot explain away. This would have meant that another is not simply entitled to an uninformed opinion about the existential state of my friend’s shoes. This would mean that there is a fact of the matter. And facts of the matter are like any pests: where there is one, there may be others. You, dear reader, may not be bothered by the possibility of a fact or two milling about in the world. But I assure you that nothing is more dangerous to any theory than certain facts. But the fact that there are facts will suffice to put an end to theory itself. Theory can offer a critique of power dynamics in the form of a perspective under which we can fly, but which has been marginalized by the dominant paradigm. This is every bit as good as flying itself, until we find an open window. If we are forced to abide in the realm of fact, those brutes -- then those facts will impinge upon our minds until we are convinced that something is true, or else tease our curiosity until we try to discover those truths. And that truth will erode our will until we believe it, and perhaps we would decide to act accordingly. Soon, we may even begin to consider evidence! And if there is evidence for (or against) claims we dislike, such as the existence of God or the resurrection of Christ, we may find ourselves in the shameless position of changing our minds about the matter. This young man was able to see down the road -- far enough to see all of this coming. Shoes...truth...Christ. Clever young minds who are capable of seeing where the path leads are capable of avoiding that path if the destination is a place they do not desire to go. I have not been clever enough to avoid this path. I could not see as far into the distance as the young man. I believed in the shoes, and so I believed there was truth, and was ready to admit as much. I was not clever enough to avoid this path, and so it would eventually lead me to a belief in Christ before I could get away. My impoverished education did not provide me with enough theory to escape the force of reality when it came to believing the sorts of things this young man wished to avoid. The foresight to predict the consequences of one’s beliefs before holding them is a powerful tool. When combined with the ability to choose one’s own beliefs at will, it means you need never about discovering that you were wrong. III. Years later, I found myself having a conversation that reminded me of this last one. This time, the parties were a young woman (an atheist) and a different friend (also a Christian) and myself. By now I had worked out the commitments of the beliefs I could not force myself to reject, and so I too was a Christian. Our conversation was about art. My friend maintained that there is beautiful art, and thus there is beauty. The young woman maintained that any allegation of beauty is simply a matter of preference on the part of a subjective, limited perspective. She was another student of theory. As you know, according to theory, all perspectives are limited and thus equal in merit. One of the delightful things about theory is that there is but a single rule of inference, and it allows for such conclusions. My logical training is unfortunately old fashioned, and thus I am not skilled in the use of the logic which belongs to theory. The best formulation of the rule that I have been able to derive is the following: Any conclusion can be asserted, provided that it is preceded by another assertion and the word “therefore.” This inferential rule is sound and complete with respect to theory, and is terrifically consistent with believing whatever one wishes. The proof of this is left to the reader as an exercise in theory. It is worth remembering that the first assertion, or the premise, is not restricted to merely dubious assertions. If it is necessary to do so, true statements can also be admitted as premises when they are available. The young woman, a student of theory and thus familiar with theory’s rule of inference, did not believe any art was more beautiful than any other. Since something is only beautiful according to a perspective, it cannot be true that it is beautiful. It can only be “beautiful according to X.” Thus nothing is better, or preferable to anything else. A quick bit of theorizing will reveal that this must be the case. If this assertion weren’t true, there would be things that are untrue, which would mean that some things are less preferable than others. But we’ve already established via theory that something is only preferable according to a perspective. And since any perspective is equal to any other perspective, therefore (per our rule of inference), the statement “X is truly beautiful” is false. This seemed odd to my friend (who also was a poor student of theory). He asked a question in full sincerity: “Is [the music of] Nicki Menaj equal in beauty to [the music of] Bach?” The reader, having been introduced to theory will know that the answer was, “there is a perfectly valid and equal perspective according to which it is equally beautiful.” I confess that I have done my best to theorize this point. But alas, my skill in theory being weak, there are many things that I cannot make myself believe. One of them is that the two passages which open this essay are equal in value, merit, or beauty. But like the young man of theory in the first encounter, this young woman was able to see what lay ahead on the road -- where my theoretical nearsightedness would have rendered it merely a hazy outline. I am impressed at her ability, not merely to see so far ahead, but to bite the bullet of affirming the ouvre of Minaj. This ability is especially impressive when one considers that the reason for affirming Minaj stems ultimately from her commitment to the aims of feminism. This appears to me as madness, and I find myself unable to know how to respond. Augustine observed when contemplating the nature of time that the hardest positions to explain or justify are often the very ones we find the most obviously true. So it is to me that the melodies of Minaj are of less value than those of Bach, and her lyrics of less value than the words of Homer. Speaking of Odysseus and insanity... IV.

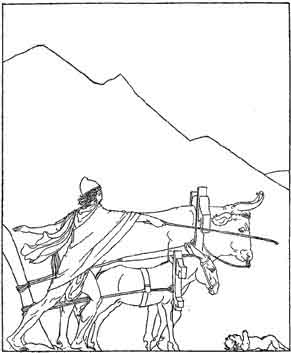

In a sudden flash, it occurred to me that the madness of the young woman and that of the young man reminded me of something. Surely, I thought to myself, no one is so truly mad as these two. And then I remembered Odysseus’ ploy to avoid fighting in the Trojan War. In the story I remembered, he went into his field, tilling up the crops that were growing and sowed salt into his fields as though it were seed. No one in his right mind would do this. Clearly, Odysseus had lost his mind, and was unfit to perform the service he had pledged to his king. Palamedes took the infant Telemachus and placed him in front of the plow. When Odysseus stopped to avoid killing his precious son, he showed that he was merely feigning his insanity.

Each time I have encountered theory, I have sought after something to place before the plow. I have sought something that will reveal the apparent madness of my interlocutors to be a feint. I have yet to succeed.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply.The CenterI write about all sorts of things. This is one of the places where I do it. Archives

January 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed